God gave man Dominion over all the Earth, not government or corporations.

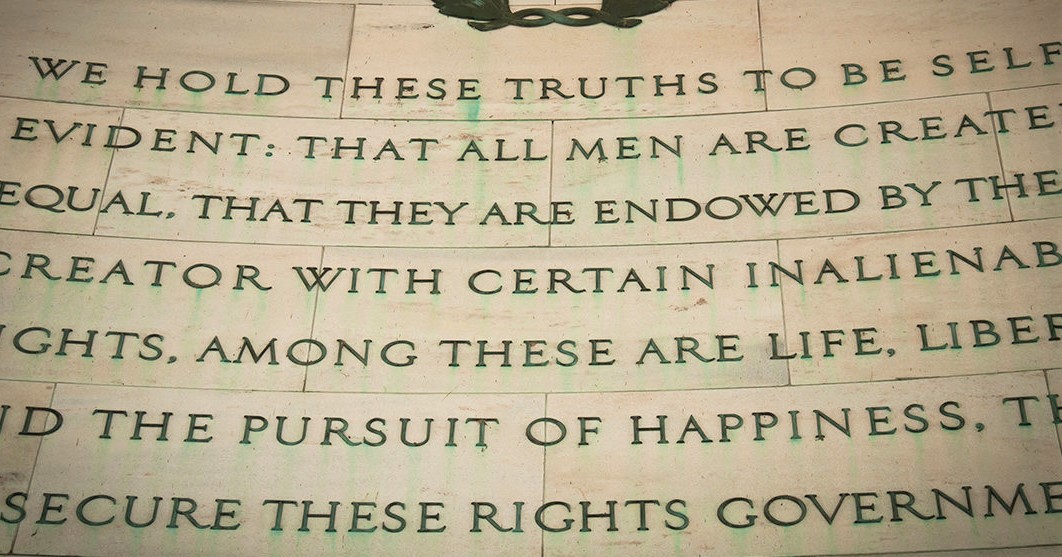

When the American Founders wrote the U. S. Declaration of Independence of 1776, they set down important philosophical principles to defend and justify their freedom from British rule and their formation of a new, independent nation, the United States of America. One key principle asserted by the Founders was the unalienable rights of mankind—the “self-evident truth” that all men “are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” What is not often recognized today is that influential European philosophers and the American Founders grounded, articulated, and affirmed the idea of unalienable rights, in large part, based on the Law of Nature and God, the Bible, and Judeo-Christian thought.

Unalienable rights are natural rights. What exactly are natural rights and unalienable rights? Natural rights are the God-given or inherent birthrights or properties of all mankind due to our nature and dignity as human beings. These rights are grounded in the Law of Nature and God, the universal moral law. These rights include, as philosopher John Locke describes in his 1689 Second Treatise of Civil Government, one’s personhood, means, and possessions—his life, body and health, liberty, labor and industry, and goods and estates. Natural rights can be classified specifically in two ways—as “alienable” or “unalienable.” “Alienable” rights or properties include an individual’s means, labor, and possessions that can be transferred–bought, sold, or given–and thus removed or alienated from the owner as he sees fit, for example, in order to make a living or to better his own or another’s life. “Unalienable” or “inalienable” rights are those properties of personhood that cannot be transferred, removed, or alienated from an individual by any person, power, or civil law without just cause. Doing so would violate the Law of Nature and God. For mankind does not have total control or authority over these properties. Unalienable rights, as recognized in the Declaration, include life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

The idea of natural rights was articulated in the 1100s and 1200s by European medieval Christian lawyers dealing with property law in the Catholic Christian church. These lawyers viewed property or dominium as a natural right based on Genesis 1 in which God creates mankind in His image and gives him dominion over the earth. Genesis 1:26-27 says, “Then God said, ‘Let us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness. Let them have dominion…over all the earth.’ So God created man in His own image, male and female [bold emphasis mine].”1 Yet the lawyers thought that while a person’s material property is transferrable or alienable, the property of his personhood such as his life is non-transferrable or unalienable. In the 1400s, liberty was also articulated as a natural right. French scholar and theologian Jean Charlier de Gerson articulated liberty as a natural right in his 1402 De Vita Spirituali Animae or The Life of Spiritual Souls. Soon after, Dominican theologians classified liberty as unalienable. Life and liberty thus came to be theologically expressed as sacred, unalienable rights of mankind.

Later, Christian thinkers of the Reformation era of the 1500s indirectly supported natural rights due to their belief that human beings, as created by God, have certain duties to God. French religious reformer John Calvin asserted in his 1536 Institutes of the Christian Religion that human beings have duties to God because they are God’s “workmanship” or masterpiece. Calvin draws this idea from Ephesians 2:10 in which the Apostle Paul expresses, “We are God’s workmanship, created in Christ Jesus unto good works, which God hath ordained, that we should walk in them [emphasis mine].” (KJV, GNV)2 Calvin thus writes, “How can the idea of God enter your mind without instantly giving rise to the thought that since you are His workmanship, you are bound, by the very law of creation, to submit to His authority?—that your life is due to Him?—that whatever you do ought to have reference to Him [emphasis mine]?”3 The idea that human beings have natural rights because of their duties to God, was asserted by reformed political writers including John Ponet in his 1556 Short Treatise on Political Power and Stephen Junius Brutus in his 1579 Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos.

Enlightenment-era British philosopher John Locke, in his 1689 Second Treatise, introduced a clear, modern explanation of natural rights which became very influential to early Americans and American founding political thought. Locke shared the view of Christian thinkers like Calvin that because human beings are created by God, they have certain duties to God. Locke went on to assert that individuals, as created by and owing duties to God, possess certain natural rights including “life, liberty, and estate” which are necessary to preserve humanity, maintain order, and perform such duties in the world. Reflecting Calvin, Locke expressed the idea found in Ephesians 2:10 that man is God’s workmanship in order to ground the principle of natural rights. He reasons,

As such, Locke asserted that man is God’s property, created for God’s and not another’s purpose and use. As a result, human beings have natural rights which they are bound to uphold. Locke was essentially saying that natural rights allow human beings—who possess a unique identity and relationship with God—to freely worship and follow God, serve as stewards for God, and fulfill their God-ordained duties and purposes on earth.

The American Founders’ understanding of natural rights was largely influenced by Locke. They believed that natural rights are the inherent gift of God, the Creator, for mankind. Civil governments may secure these rights, but they do not originally grant them. As such, governments cannot take away these rights without just cause, and men may justly defend their rights for self-preservation. Importantly, the Founders recognized that removing God as the source of natural or human rights would endanger these rights and freedoms.

American Founder and revolutionary leader Samuel Adams, drawing from Locke, addressed the American colonists’ natural rights to life, liberty (including religious liberty), and estate in his 1772 revolutionary pamphlet, Report on the Rights of Colonists. Because God gives man life and dignity, Adams argued, man has a natural right to life. And as God gives man reason and free will to reflect and choose, man has a natural right to liberty—including political and religious liberty. Man also has a God-given right to his labor and possessions for his survival. Adams, like Locke, defended these rights by their origin in the Law of Nature and God. He writes of liberty, for example, “‘Just and true liberty, equal and impartial liberty’ in matters spiritual and temporal is a thing that all men are clearly entitled to by the eternal and immutable laws of God and Nature, as well as by the law of Nations & all well-grounded municipal laws which must have their foundation in the former.”5 Adams further recognized that the Bible supports these rights, that they “may be best understood by reading and carefully studying the institutes of the great Lawgiver and head of the Christian Church [Jesus Christ] which are to be found closely written and promulgated in the New Testament.”6

American Founder and primary author of the Declaration, Thomas Jefferson shared the long-held view that life and liberty were natural, unalienable rights. He acknowledged that such rights were the gift of God, stating in his 1774 Summary View of the Rights of British America, “The God who gave us life, gave us liberty at the same time. The hand of force may destroy, but cannot disjoin them.”7 However, unlike many Calvinists in America and England, Jefferson did not classify man’s “estate” as unalienable. Rather, in line with the moral-sense thinkers of the Scottish Enlightenment—including Francis Hutcheson, David Hume, and Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui—Jefferson defined man’s goods, possessions, and fruits of labor as transferrable or alienable property. As such, he did not list “estate” as an unalienable right in the Declaration but instead listed the “pursuit of happiness.”

American Founder, Federalist Papers author, and architect of the U. S. Constitution and Bill of Rights, James Madison shared Locke’s idea that natural rights were granted to mankind based on their duties to God. In speaking of religious liberty, for example, Madison wrote in the Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776, “Religion, the duty we owe to our Creator and the manner of discharging it, can be directed by reason and conviction, not by force or violence. Therefore, all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion according to conscience. It is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love, and charity towards each other [emphasis mine].”8 Madison reasserted in his 1785 Memorial and Remonstrance this idea that inherent, unalienable rights such as religious liberty are based on mankind’s natural duties to God, which exist before civil society: “Religion must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man. [This right] is unalienable because the opinions of men…cannot follow the dictates of other men. What is here a right towards men is a duty towards the Creator. This duty is precedent to the claims of civil society

American Founder, lawyer professor, and U. S. Supreme Court Justice James Wilson also supported the principle of natural and unalienable rights in his 1790-1791 Lectures on Law and in his 1793 court decision Chisholm vs. Georgia. In his Lectures, he observed that all human beings possess natural rights which are upheld by the universal moral law of God and Nature. He writes, …

In Chisholm vs. Georgia, Wilson, like Locke, referenced ideas from Genesis 1, Ephesians 2:10, and Psalm 139:14 (in which the individual is described as “fearfully and wonderfully made”). He thus defended from the Bible a person’s God-given rights that should be protected by civil government. Likewise expressing the idea of man as God’s workmanship found in Ephesians 2:10, Wilson expounds, “MAN, fearfully and wonderfully made, is the workmanship of his all perfect CREATOR. A State, as useful and valuable as the contrivance is, is the inferior contrivance of man and from man’s native dignity derives all its acquired importance [bold emphasis mine].”11 Because the state consists of the people, Wilson essentially asserted, if the state diminishes the rights and dignity of the individual citizen, it basically also diminishes the rights of the state itself.

The principle of God-given natural, unalienable rights of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” is a key philosophical principle expressed in the U. S. Declaration of Independence and reflected in the U. S. Constitution. Taking up Locke’s worldview and arguments, the American Founders grounded man’s natural rights in the “Creator God” and the “Law of Nature and Nature’s God.” They considered these rights to be a gift from God granted to humanity as God’s image-bearing masterpiece, His workmanship. Such rights allowed mankind to fulfill their God-ordained duties in life. Indeed, the Founders were acutely aware that removing God or the moral law as the grounding of natural rights would place those rights in jeopardy. For if one could separate these rights from the divine source, one could justify taking them away at will for any reason. Jefferson pressed the point in his 1781 Notes on the State of Virginia: “Can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with His wrath?”12 The principle of natural, unalienable rights in America’s founding philosophy is, affirms Steven Waldman in his 2008 Founding Faith: Providence, Politics, and the Birth of Religious Freedom in America, the “best argument that Judeo-Christian tradition influenced the creation of our nation